Giverny - the village of Monet's Garden

This is a favourite place to visit, the beauty and tranquility coupled with the history make it a place everyone should see when visiting France. Lots of artists and art galleries can be found in this delightful village, made famous by Calude Monet and his fabulous garden which he claimed was his best work of art.

Planning the garden

The story of why and how Monet planned and planted the garden as he did is as intriguing as its result. Monet’s passion for gardening almost equaled his devotion to art, but it was only when he arrived in Giverny in 1883 that he had both the financial means and sufficient land (nearly 2.5 acres) to indulge his enthusiasm. He deemed himself “dazzled and delighted” at the prospect.

Avant garde

As avant-garde a gardener as he was an artist, Monet designed his garden with the vignettes of flowers, trees and water that he wanted to paint. “Traditionally, a landscape artist goes into the country, finds a scene and then paints it,” explains Marina Ferretti, the museum’s curator, “even if he rearranges and re-composes it for his painting. I don’t think there is another example in art history of a painter who created a natural landscape that he later painted. Curiously, Monet was the father of Impressionism, of the spontaneous study of nature as it is. But here, he composed his picture directly with the nature he loved.”

The re-design

When the artist set about redesigning the property—an abandoned cider farm—he kept the central allée that bisected a garden that was mainly an apple orchard. But he progressively ripped out the box hedge and knocked down the dark spruces and cypress trees that would overshadow the beloved flowers he wanted to plant and paint.

A work of art

Painting was put on hold while he dug, seeded, weeded and hoed, doing a lot of the work himself—at Giverny he rose at dawn and usually was in bed no later than 9 pm. His eight children—his two sons by his first wife Camille and his second wife Alice’s four daughters and two sons from a previous marriage—were in charge of the evening watering. Friends like actor Sacha Guitry, French statesman Georges Clemenceau and his fellow artists Rodin and Bonnard came for lunch and a walk in the garden. Gustave Caillebotte, also both gardener and painter, crossed the Seine by boat from his home in Petit-Gennevilliers to exchange horticultural tips and cuttings.

Head gardener

“Monet was his own head gardener,” Gall declares. “He was obsessed by the beauty of flowers and the composition of his garden, he was an inventor and a researcher. He had a library of horticultural books, periodicals and plant dictionaries in French, English and German, so he could keep permanently informed of new plants that could represent a color or an atmosphere. He planned the garden like motifs for his pictures and his paintings became the inspiration to continue the garden.”

Le Clos Normand

The carefully tended planting of Le Clos Normand, however, did not immediately translate onto canvas. “The process was long and complicated,” says Ferretti. “It took almost 20 years, buying extra land and getting authorizations to dig and expand his pond and to build the Japanese bridge. And the plants had to grow. It was only when everything was in place that Monet started to paint his garden.”

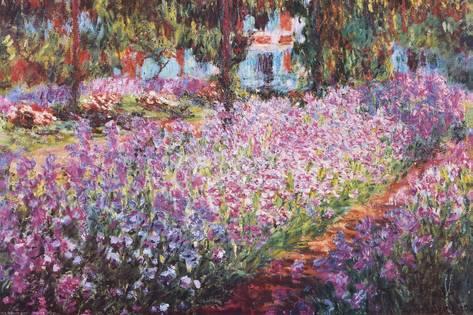

Jardin a Giverny

The only known early painting of the garden, Jardin à Giverny (Dans le Jardin de Monet), dated 1887-91, is not by Monet but by American artist John Leslie Breck, who was part of the American colony in Giverny.

Monet's travels

While his garden grew, Monet traveled and painted elsewhere. Farther-flung travels often provided inspiration for his planting. In 1886, he complained that his palette paints could not capture the stunning hues of the red and yellow blooms in the Dutch tulip fields; back home, he recreated concentrated blocks of colors in 38 “paint-box” flower beds. The orange, lemon and palm trees in the Italian coastal town of Bordighera not only spurred his magnificent 1884 Sous les Citronniers (Bordighera), but also the idea of the astonishing profusion that characterizes the garden.

Japanese peonies

Monet’s own first Impressionist painting of the ensemble of the garden, in 1895, features a young woman. A modernist study of peonies followed in 1896. “He was very proud of his Japanese peonies,” says Ferretti.

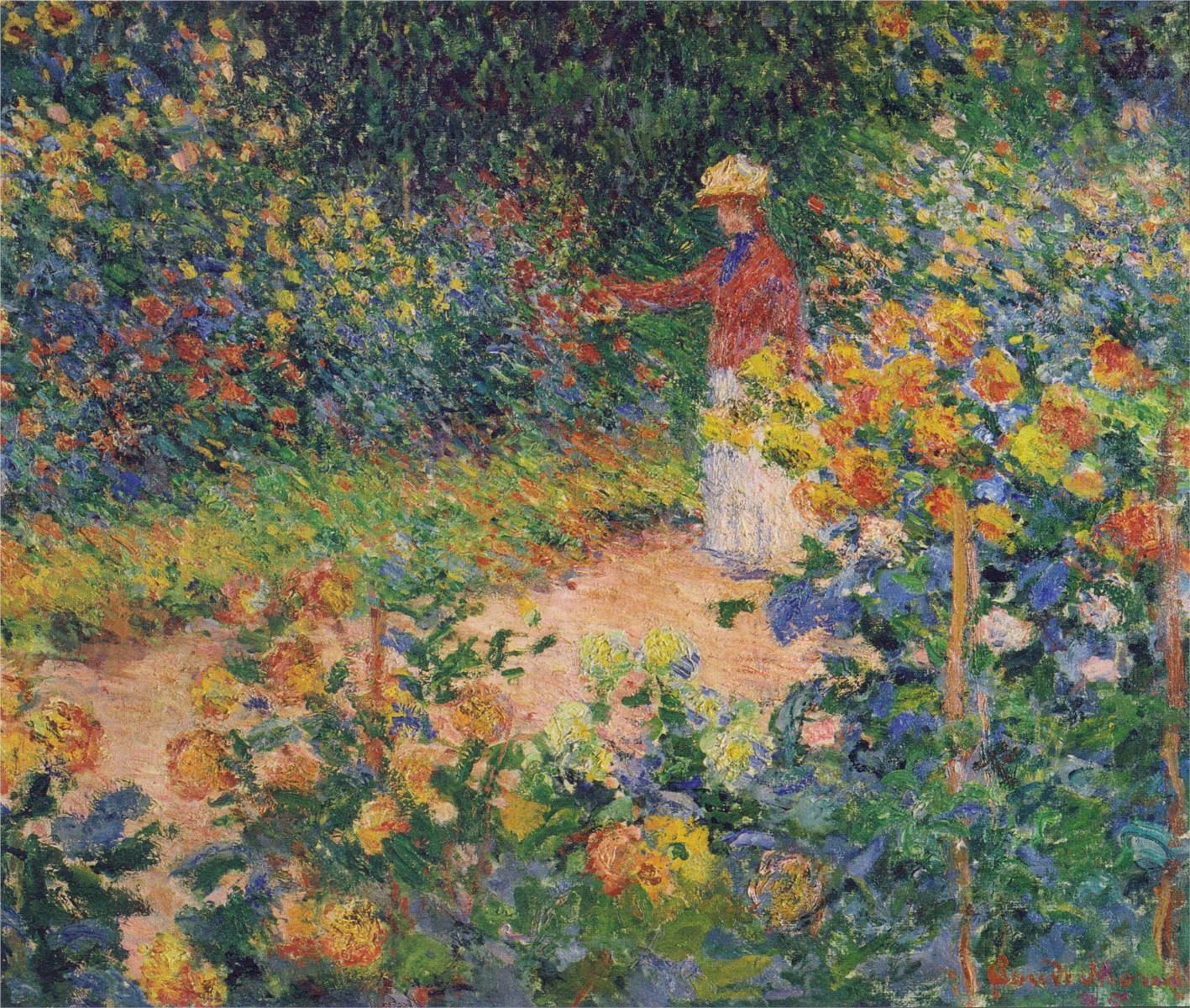

The garden pond

The approaching turn of the century marked major changes in both Monet’s garden and his art. Armed with resources from American collectors who were avidly buying his works (the reason why there are so many Monets in the US today, says Gall), he bought a strip of marshy prairie south of his land so he could create a pond. This involved diverting the Ru, a branch of the River Epte, into a design of curves and circles that contrasted with the rectangular beds and straight paths of the first garden. To link the two, he planted an already mature copper beech in a direct perspective of the first garden’s Grande Allée.

The water lilies

When Monet discovered the water lily, it too became an obsession. “He bought and acclimatized all sorts of exotic varieties with extraordinary colors that needed more heat than they could get from the Normandy sun,” Gall recounts. “By building a wall, he created a smaller pond—the water was only about a meter deep—and tried heating it with pipes from a system installed behind the trees. But he finally had to abandon the effort.”

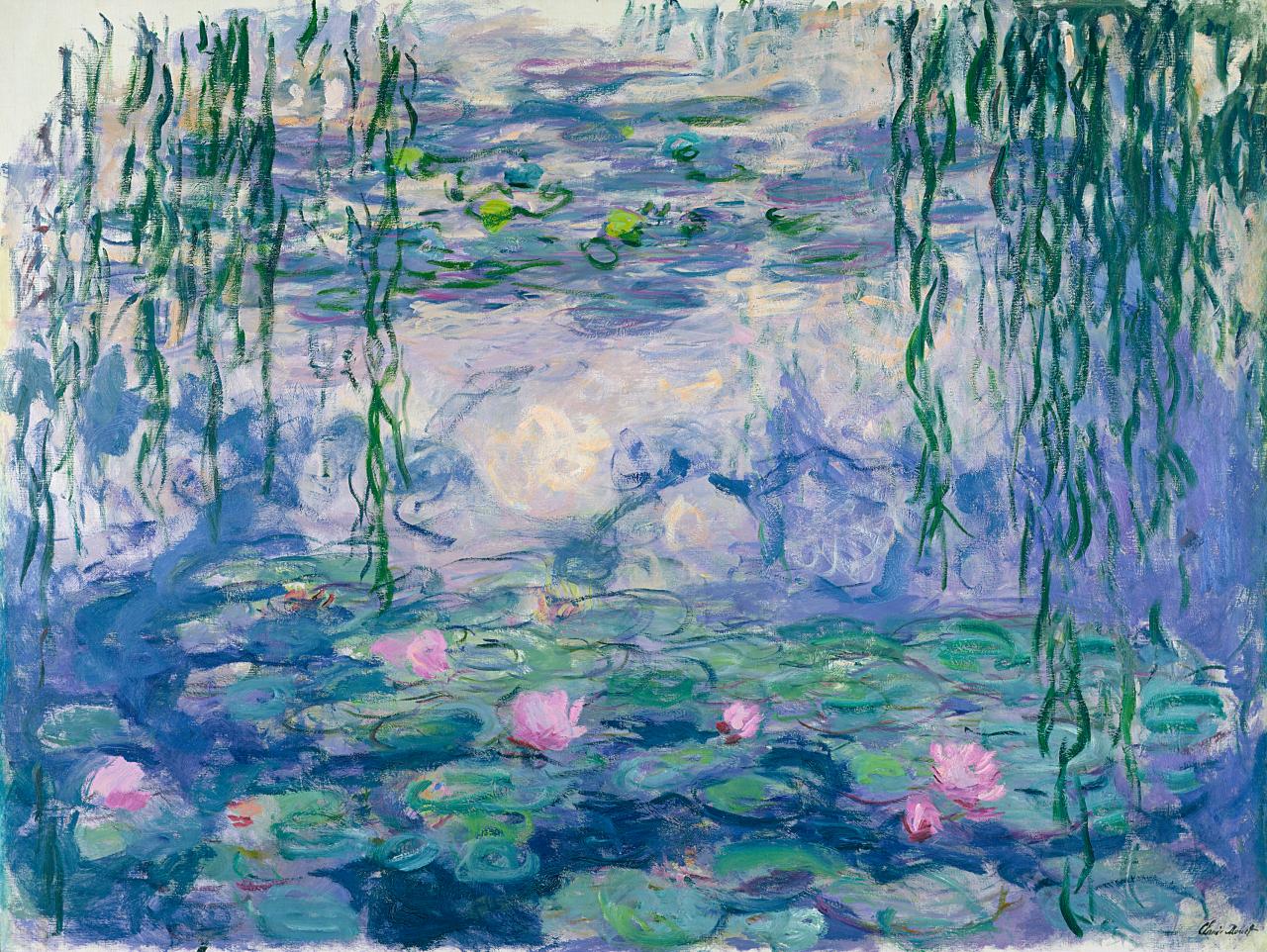

The Japanese bridge

Monet began to paint a series of the Japanese bridge, “the celebrated paintings from the Musée d’Orsay,” Ferretti explains, “with a complete view of water, bridge and the surrounding vegetation. Very quickly, he concentrated more and more on the reflection on the water’s surface, a mélange of light, greenery, water and sky. This universe was less easily identifiable, more fluid.” He changed the simpler, smaller formats and small rapid brushstrokes of the Impressionist period to vast, long canvases that grew bigger and bigger and were painted with generous, sweeping gestures.

“From there, he took off on the adventure of the water lilies painted for the Orangerie museum in Paris, a new and astonishingly modern artistic track,” Ferretti confirms. “His painting becomes unfocused, complex and it no longer has perspectives. It is very far from traditional Western painting. Little by little we are submerged in a universe of paint. It’s at the limit of abstraction. Many abstract artists claim his influence.”

And yet, she points out, “He was a man of the 19th century, a realist painter, he couldn’t do that alone. He needed to create that water lily pond before he launched into the immersion in blue and green.”

Join us for an 8-day Normandy Small Group Tour and see Monet's garden for yourself

information source France Today